One of five Caldecott Honor books in 1939, Wee Gillis proves that you don't need a lot of words or color to have an impact. Robert Lawson's black-and-white illustrations help us connect with the characters and setting in Munro Leaf's simple story of a young Scottish boy who must choose between two very different ways of life.

The Story of Wee Gillis:

Torn Between Two Worlds

First, let's get one thing clear, Wee Gillis is not actually our title character's name. It's "Alastair Roderic Craigellachie Dalhousie Donnybristle MacMac, but that's too long to say, so everybody just called him Wee Gillis." While we assume the "Wee" refers to his size, there is no explanation for how the relatives came up with Gillis. It's not important to the story, of course, but my curiosity got the better of me, so I Googled it and found two meanings: 1) young goat; and 2) servant of Jesus. Either one seems fitting, especially since (although it's never directly stated), Wee Gillis is an orphan.

Growing up without your parents is difficult enough, but that's not the source of Wee Gillis's conflict in the book. Instead, he finds himself caught between two worlds: 1) the Lowland life of his mother's relatives with their farms and cows; and 2) the Highland life of his father's relatives filled with stag hunts. He spends time with both sides of his family, learning their ways. In so doing, he becomes very strong, especially in his lungs because of the need to both shout for the cows through the mist and hold his breath for long periods to avoid scaring the stags.

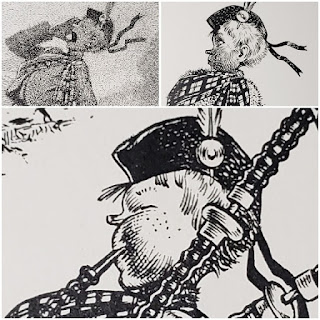

Despite the challenges of each setting, Wee Gillis has affection for both places and both sides of his family. The feeling is mutual, and when he comes of age, Wee Gillis must choose between the two. On the big day, his Uncle Andrew from the Lowlands and Uncle Angus from the Highlands take him halfway up the hill between the two clans. Each makes a case for join their side of the family. Wee Gillis is truly torn, hilariously setting the two grown men into a childlike fits, complete with foot-stomping and jumping. There argument is interrupted when a forlorn bagpiper stops for a rest. Distracted by the passerby, the men stop fighting and learn that the musician is in despair because he made a set of bagpipes that are too big for him. Both uncles fail to fill the bags with enough air to play them. Finally, Wee Gillis gets his chance, and as the picture below humorously shows, he is successful; notice the feet in the corner, showing one of the uncles who "fell of their rocks in surprise":

Such a talent needs to be used, so the man offers to teach Wee Gillis how to play, and this becomes his profession. For the rest of his life, Wee Gillis visits both the Highlands and the Lowlands, playing the biggest bagpipes on Earth -- and building his home halfway up the great hill, right between his two worlds.

Lawson's Art in Wee Gillis:

Where Setting and Characters Come to Life

Just as he did in the 1938 Caldecott Honor Four and Twenty Blackbirds, Lawson shows mastery of both the large and the small. His landscapes are sweeping and pull you in, making you feel a part of the countryside. In fact, it's so well executed that you oddly don't miss the color (at least I didn't, but then I also like black and white movies).

As impressive as these images are, it's Lawson's attention to much smaller details that makes the story come to life. As in Four and Twenty Blackbirds, facial expressions are key, but even more so here. The collage below shows one of my favorite expressions that he gives Wee Gills, as he waits in hopeful anticipation to have a chance to play the oversized bag pipes. Just above him, though, are a few of the faces that dot the background of other scenes: an old man and little girl hearing the shouting match between Wee Gillis's Highland and Lowland family members, and children listening to him play the bagpipes at the end of the story. Shock and curiosity in the first two are and palpable as the enjoyment and mischief in the third.

Below are more examples of great faces in the story. Along the top row: 1) You can just feel the irritation of the Lowland relatives as they wait for Wee Gillis to return with the cows; 2) You can almost hear Wee Gillis wondering when the lecture will end, and 3) later we feel his anxiety over having to choose which set of relatives to live with permanently.

My personal favorite face, appears below. It depicts one of the Lowland relatives as they mock the Highland way of life. To me, the expression on Wee Gillis perfectly captures how children look as they politely listen, somewhat amused by how the adults are acting but not really processing (or maybe not agreeing with) everything that they say. The real treasure here, though, is the relative. You can almost hear his think, Scottish-accented, "Get a load of them!"

Another important contribution that Lawson makes to the book is using his mastery of facial expressions to highlight the development of Wee Gillis's strong lungs. Mentioned only three times in the 46 or so pages before the bagpiper shows up in the story, it stands out thanks to Lawson's imagery, which is not only amusing but also very helpful for young readers (or older ones with a lot one their mind):

A final note on the artwork: Looking at the pictures above, I cannot help but notice the ribbons on Wee Gillis's hat blowing in the wind. Again, Lawson shows a superior ability to capture movement, which is also apparent in the example below, where we can sense Wee Gillis's awkward pre-teen gait, his fidgeting with his clothes, and the movement of the fabric in response to his actions and the wind.It's a minor detail, but it's a collection of small visual moments like this one that animate the story and make the book a special experience.

No comments:

Post a Comment